Quantifying Fashion Data

The fashion industry is very different to domains where recommender systems originated in a number of ways. Here we examine the most significant characteristics, and dive into the challenges that this causes a fashion recommender system.

Brief History of Recommender Systems

Since the 2000s, recommender systems have received increased attention as online commerce has grown. A lot of research has gone into developing recommendation algorithms. This research has constantly improved the way we choose relevant products to show to which customers.

An important aspect in this development was how the recommendation problems were framed. The datasets used to experiment and measure the success of different approaches came primarily from other domains. Particular examples are movies (Netflix, MovieLens etc), music (Spotify, Last.fm etc), books (Amazon etc) and research articles (CiteULike etc).

One of the biggest motivators was the 1 million dollar Netflix prize of 2006-2009. For this challenge, research teams competed to build the best recommender on a Netflix dataset. But most of the established recommendation approaches to date were driven by experimenting on datasets from movies, music and print domains.

These datasets shaped the direction that researchers would take to solve the recommendation problem. They would also dictate whether one research direction was pursued over another.

Fashion Recommendation Systems

When building Dressipi’s fashion recommendation engine, standard product recommendation engines did not work well for the fashion domain. The only really developed AI recommendation algorithms were those most successful in traditional domains. These are the foundation for the standardized approaches available in code libraries today.

There are implicit assumptions built into the AI recommendation engines as a result of this process. They work well for the characteristics of the datasets they were built with and evaluated on. However, these characteristics are not the same in many other retail domains, and are especially different in fashion.

Fashion vs Other Domains

Firstly, we will examine the statistics that we can use to quantify the characteristics of fashion data. We will compare this data with the music and movie domains. For example:

- How many items are available at any one time?

- How many new items become available per month?

- How many items leave the product catalog per month?

- How long is an item usually available for?

- How many of each item are available?

We have compiled these numbers for Netflix and Spotify as representatives of movie and music domains. For the fashion domain, we take an aggregation of the data we have seen across the fashion retailers we work with. The differences in characteristics across industries are so large that even these rough aggregations suffice.

1) Changes in Product Catalog

The table below shows how many items are available at any one time. It also shows what percentage of the product catalog is changing each month, by either adding or removing items.

The movie and music domains have a large, consistent product catalog from month to month. Their growth is continuous, and incremental. Only 5% of products are in the ‘new item problem’ (‘cold start’) group. This means 95% of candidate items that we could recommend have historical data of user interactions available.

At the same time, less than 2% of items get removed every month. The rest remain available to be recommended and for users to interact with. The majority of historical customer data remains directly relatable to new user interactions. This is due to the same items being available then and now, without needing to use content data.

On the other hand, in fashion, we have a very dynamic product catalog. Every month, on average about a third of products are discontinued and equally as many new products get added.

The cold start problem affects on average 33% of the product catalog. This number can range between 20% to as high as 50%, depending on the retailer. With as many items getting removed, we are also at risk of losing a large chunk of data to learn from.

If we look at larger time frames, almost all items available in the previous period won’t be available anymore. There are staple items - basics - that remain in the product catalog for longer. But even those get slightly changed and re-released as new items. When comparing a seasonal catalog to the previous year, for example, usually less than 10% of items are still available.

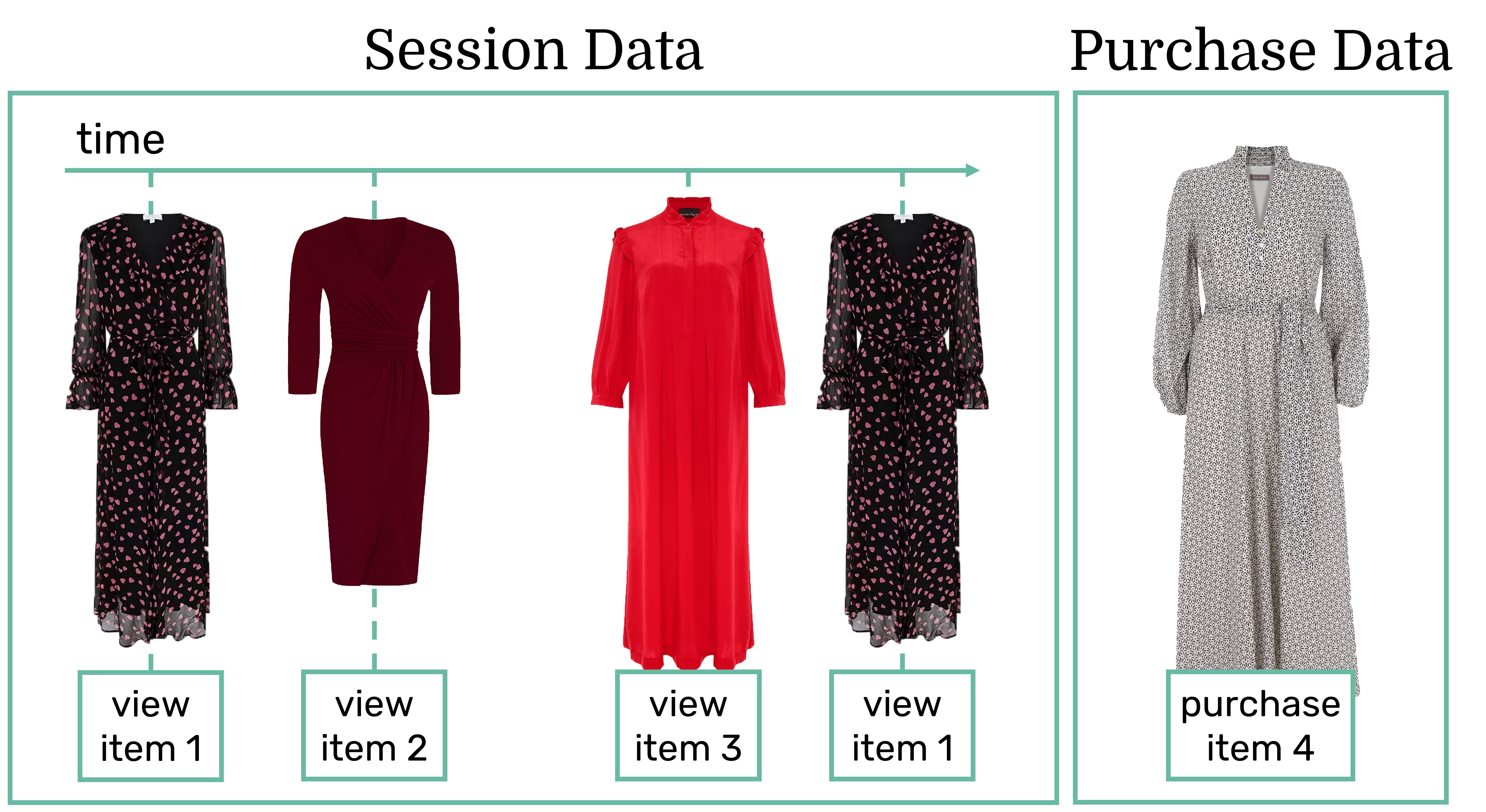

To address this problem, the lean towards content based recommenders is much bigger than other domains. In fashion, the most valuable information is in the image.

So, we need a way to extract the content data from the image. This will turn the image into something our recommender can use. At Dressipi, we have a process of labeling items with apparel specific product attributes.

Find out more about why accuracy and specificity of garment data is so critical to drive better algorithms here.

2) Stock and Lifetime of Products

The other aspect we examine is how many of each item are available to purchase. We also consider how long each item remains in the catalog. For a non-digital comparison, we looked at the print books domain.

For Netflix and Spotify, this problem does not really exist. Their stock is unlimited since the products are digital. Additionally, the lifetime of a product is theoretically infinite (we have taken this to mean 5 years). The median item lifetime for clothing items is only 70 days.

This goes hand in hand with the big product catalog changes we have observed and is the reason behind them. The short lifetime makes sense when we consider seasons. Retailers want to offer relevant items to their customers, and what clothing is relevant largely depends on the season.

Books typically have a print run anywhere between 15 to 25 thousand. In fashion, the median stock quantity for clothing items in a retailer’s catalog is usually around 100. This is then split across multiple sizes, so the effective available stock for users of a given size is even lower.

For the recommender system, this means that there are a lot of items available in low quantities. These products are only available for a relatively short period of time. So the recommender has to adapt quickly, and start making fairly good predictions on limited interaction data.

We can’t wait until the item has been bought enough times to build up a solid data profile. This is because by this time, most of the item stock is already gone. However, if a recommended item is bought but then returned, we have wasted a quantity of the item. The item may have been removed from the catalog by the time the return is fully processed.

The challenge is to be able to make accurate predictions within a very short period of a new item being released. This means using a very small amount of direct data on the item in question. This is another reason why content data and content-based approaches are so important in fashion.

In other domains, content data is used to improve accuracy by an incremental amount. This allows them to accumulate enough direct interaction data for the more precise interaction based approaches to work accurately.

Seasons add another complication. When a new season of products are released, in terms of content data, their most similar products are a year old. That is a pretty long time in fashion. Taste, lifestyle, body and trends all change over time, so making accurate predictions based on year-old data is tricky.

At the same time, using more recent data poses another problem. If someone likes sleeveless dresses in summer, they may not want them in winter. Our content-based approaches have to be developed with these characteristics in mind.

Conclusions

When building apparel recommendation systems, we cannot use generic machine learning algorithms that were built for movies, music and books. These systems are not equipped to deal with the conditions that are specific to fashion.

Machine learning recommendation systems built on and inspired by datasets from Netflix, Spotify etc have their own interesting characteristics. They also address their own industry specific problems very well. However, apparel retail poses a very different set of challenges. These are challenges that we at Dressipi have specifically understood and addressed with our AI fashion recommendation systems:

- High product churn is made even more tricky as catalogs are very dynamic.

- The cold start problem is much more pronounced, so using content data is critical.

- Short product life spans mean recommenders have to react to new items quickly.

At Dressipi, we have enjoyed - and been recognized for - addressing these challenges. We recently hosted the ACM Recommender Systems challenge (RecSys), which highlighted the need for apparel adapted recommendation approaches.

Read part 2 of this blog here. There we discuss how consumer behavior has its own impact on clothing recommendation algorithms.